Drug shortages aren’t just inconvenient-they’re dangerous

When a hospital runs out of a critical antibiotic like vancomycin or a life-saving chemotherapy drug like cisplatin, doctors don’t have time to wait for a solution. Patients delay treatment. Some skip doses. Others end up in emergency rooms because there’s no alternative. In 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration tracked over 300 active drug shortages, with 40% of them involving injectable medications used in ICUs and cancer centers. These aren’t rare glitches-they’re systemic failures in a supply chain that’s been stretched thin by globalization, manufacturing bottlenecks, and rising demand.

Why do drug shortages keep happening?

The root causes are simple but hard to fix. Most generic injectable drugs are made in just a few factories, often overseas. If one plant shuts down for an FDA inspection-or if a key raw material gets delayed-the whole country feels it. In 2023, a single manufacturer in India halted production of phenylephrine, a blood pressure drug used in over 90% of U.S. hospitals. Within weeks, emergency rooms were rationing doses. Meanwhile, profit margins on generic drugs are razor-thin. Companies don’t invest in backup lines or extra inventory because there’s no financial upside. And when demand spikes-like during flu season or a pandemic-the system cracks.

Health systems are building buffer stocks

One of the most direct fixes? Keeping extra supplies on hand. Hospitals that used to order drugs just-in-time are now holding 30 to 60 days of safety stock for high-risk medications. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center started stockpiling 45 days’ worth of key chemotherapies in 2023. They now have a digital dashboard that tracks inventory levels across all 12 of their clinics. When stock dips below 20%, the system auto-orders replacement. It cost them $2.1 million upfront to build the system, but they cut emergency purchases by 68% in 2024. That’s $4.7 million saved in last-minute, premium-priced orders.

They’re diversifying suppliers-fast

Going all-in on one manufacturer is a gamble. Leading health systems are now requiring at least two FDA-approved suppliers for every critical drug. Kaiser Permanente’s pharmacy team now vets at least three vendors for each high-demand medication. In 2024, they switched from a single-source supplier of epinephrine to two new manufacturers-one in the U.S., one in Europe. When the original supplier had a quality issue, the transition took less than 72 hours. No patient care was disrupted. That kind of agility used to take six months. Now, it’s standard practice.

Pharmacists are taking charge of substitutions

When a drug is out of stock, pharmacists don’t just sit and wait. They’re actively finding safe, FDA-approved alternatives. At Cleveland Clinic, pharmacists now have pre-approved substitution lists for over 80 high-risk drugs. For example, if dobutamine isn’t available, they can switch to dopamine or norepinephrine based on patient weight, kidney function, and heart rate-all standardized in a digital protocol. In 2024, their pharmacy team managed 1,200 substitution events without a single adverse event. That’s not luck. It’s training. Pharmacists now get quarterly updates on substitution guidelines and real-time alerts when a drug is flagged for shortage.

Technology is predicting shortages before they happen

Some health systems are using AI to see around corners. Intermountain Healthcare built a predictive model that pulls data from FDA shortage reports, global raw material shipments, weather patterns affecting overseas factories, and even social media chatter about drug rumors. The system gives a 30-day warning before a shortage hits. In 2024, it flagged a potential shortage of propofol two weeks before the FDA announcement. The hospital ordered extra stock, redistributed inventory across its 22 facilities, and trained staff on usage limits. They never ran out. The model has since been expanded to track 140 critical drugs. Its accuracy rate? 89%.

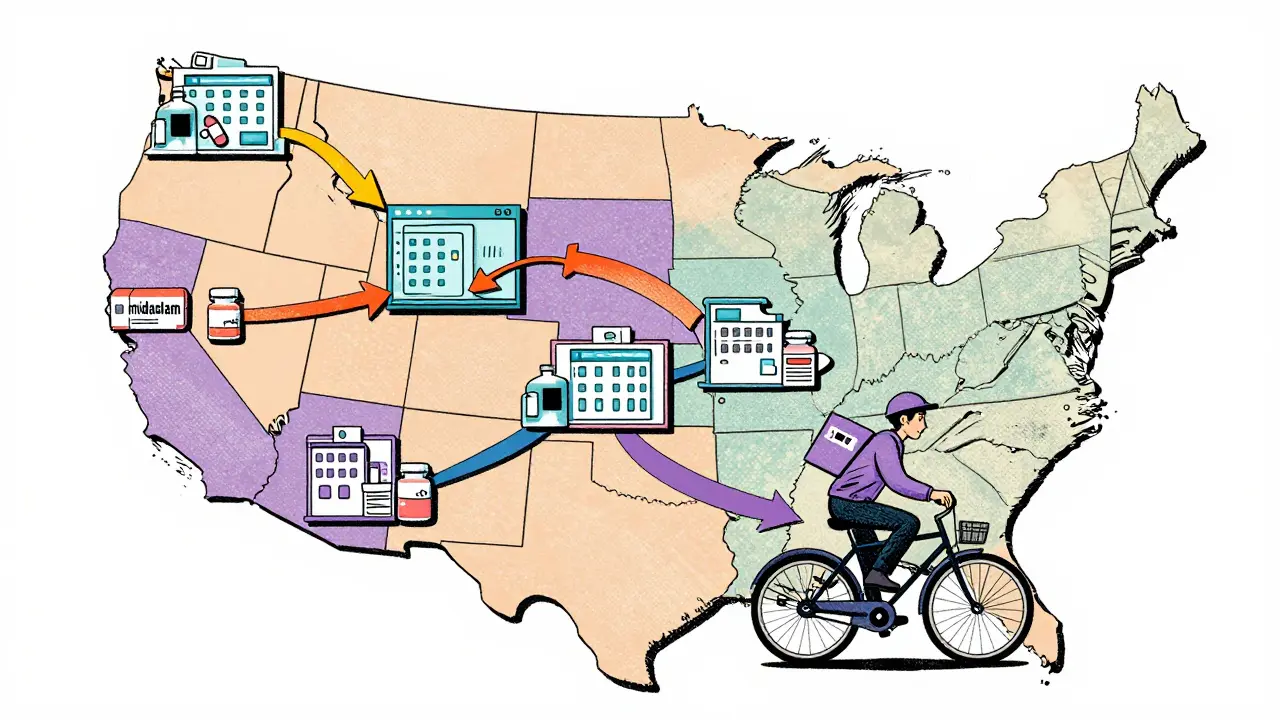

Collaboration is replacing competition

Hospitals used to hoard information. Now, they’re sharing. In 12 states, health systems have formed regional drug shortage coalitions. In the Midwest, 47 hospitals share real-time inventory data through a secure portal. If one hospital runs low on midazolam, another can transfer a shipment within hours. No paperwork. No billing. Just a text alert and a courier. The coalition, launched in 2023, reduced regional drug shortages by 41% in 18 months. The American Hospital Association is now pushing for a national version. The goal? Make scarcity a shared problem, not a hospital-by-hospital crisis.

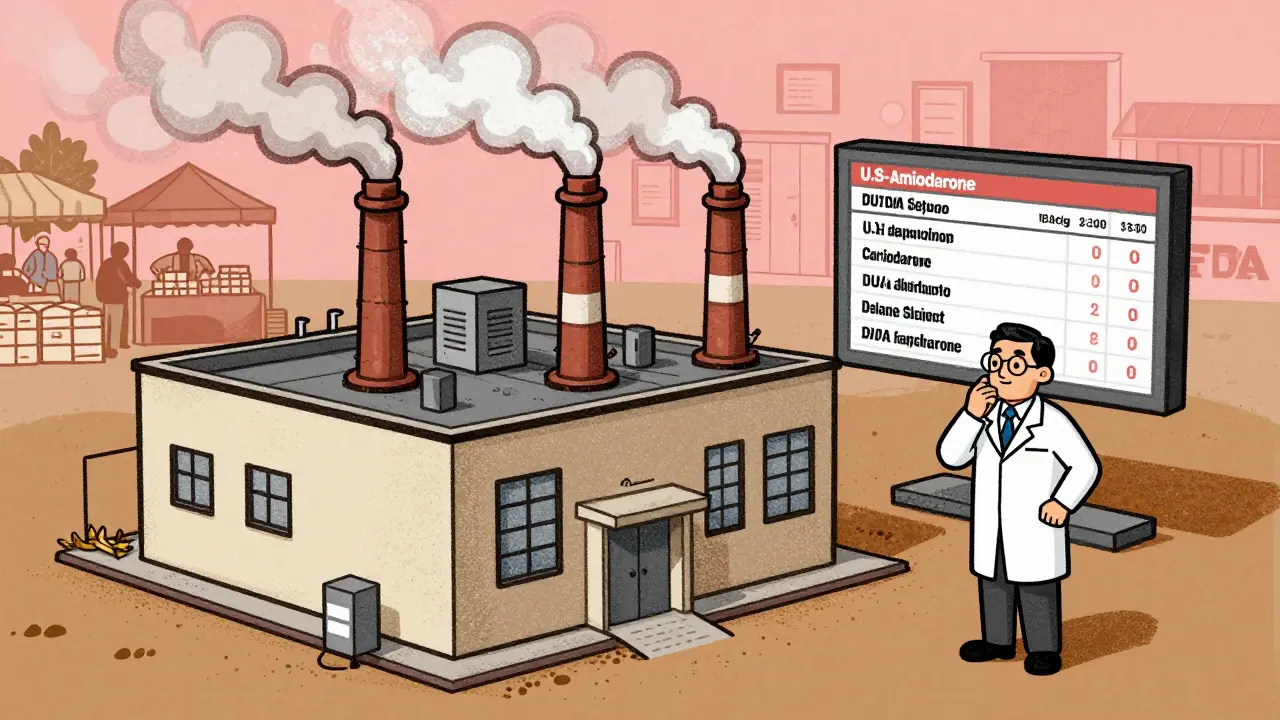

Regulators are changing the rules

The FDA is no longer just reacting. In 2024, they started requiring manufacturers to report potential supply issues six months in advance-not three. They also fast-tracked approvals for new generic drug makers. In 2023, only 12 new generic injectable manufacturers got FDA approval. In 2024, that number jumped to 31. One of them, a small U.S.-based plant in Ohio, now supplies 15% of the nation’s amiodarone, a heart rhythm drug that was nearly impossible to get in 2022. The FDA also started publishing a public dashboard showing which drugs are at risk, how long shortages are expected to last, and where alternatives are available.

Patients are being informed-before it’s too late

Health systems are no longer hiding shortages from patients. At Mayo Clinic, if a patient’s medication is on the shortage list, their doctor explains the situation during the appointment. They show them the alternative options, why it’s safe, and how it’s being monitored. Patients get a printed card with contact info for the pharmacy team if they have questions. This transparency reduces panic. It also builds trust. In a 2024 survey, 78% of patients said they felt more confident in their care when they understood why a drug changed.

What’s still broken?

Not everything is fixed. Rural clinics still struggle. Many don’t have the budget for safety stock or AI tools. And some drugs-like those made from rare biological materials-still have no alternatives. The biggest gap? Workforce. Pharmacists and nurses are stretched thin. A 2025 survey found that 61% of hospital pharmacists are spending more than 20 hours a week managing shortages instead of counseling patients. Without more staff, even the best systems can’t scale.

The future: Prevention over panic

The most successful health systems aren’t just reacting-they’re preventing. They’re investing in domestic manufacturing, supporting small drug makers, and tying supplier contracts to inventory transparency. Some are even funding research into new drug formulations that use more stable ingredients. The goal? Make shortages the exception, not the norm. It’s not about having more drugs. It’s about having smarter systems. And that’s the real fix.

14 comments

Chris & Kara Cutler

This is SO needed! 🙌 I work in oncology and saw a patient cry because they couldn't get their chemo on time. We started stockpiling last year and it changed everything. No more panic orders. Just calm, collected care. 💪❤️

Rachel Liew

i just wanted to say thank you to all the pharmacists out there. you guys are the real heroes. i had a friend who got switched to a different drug and she was so scared but her pharmacist sat with her for 20 mins and explained everything. made all the difference. 🙏

Lisa Rodriguez

Honestly this is one of the most hopeful things ive read all year. I used to think drug shortages were just inevitable but seeing hospitals actually work together? That’s huge. The Midwest coalition thing? I’m telling all my nurse friends about it. We need this everywhere. And the AI predictions? Mind blown. 🤯

Lilliana Lowe

While the initiatives described are commendable, they remain superficial band-aids on a systemic wound. The FDA’s six-month advance notice requirement is laughably inadequate when global supply chains are governed by profit-driven oligopolies. True reform requires breaking the generic drug monopoly and nationalizing critical manufacturing-something no entity in this article dares to name.

Melissa Melville

So basically, instead of letting people die, we’re… doing the right thing? Wow. Groundbreaking. 🤦♀️ I’m just glad we’re not pretending this is normal anymore. Also, who’s paying for all this? Taxpayers? Because I’m starting to see why my insurance premium went up.

Deep Rank

i read this whole thing and i just feel so sad. like why does it have to be this hard? why do we have to rely on some guy in ohio making amiodarone? why cant we just make drugs in every state? why do we let companies be so lazy? i work in a small clinic and we get stuck with expired meds because the new ones never come. its not fair. and the ai thing? sounds cool but what if it messes up? what if it says its safe but its not? i dont trust tech. i trust people. and people are tired.

Bryan Coleman

Been in hospital pharmacy for 18 years. This is the first time I’ve seen real progress. The substitution protocols? Lifesavers. The real win? Pharmacists aren’t being treated like order-takers anymore. We’re clinical decision-makers. Finally.

Nidhi Rajpara

The article presents a highly optimistic view of the current situation, which is misleading. The FDA's increased approvals of generic manufacturers do not equate to improved quality control. Many of these new entrants lack the infrastructure to maintain consistent sterility standards. Furthermore, the claim of 89% accuracy in AI prediction is statistically dubious without disclosure of the validation dataset. Caution is advised.

Donna Macaranas

I’m just glad someone’s finally talking about this. My mom’s on a drug that keeps her alive and we almost lost it last winter. The fact that hospitals are sharing now? That’s the kind of change that matters. Not flashy tech. Just people helping people.

Jamie Allan Brown

The regional collaboration model is quietly revolutionary. In the UK, we’ve been doing something similar with blood products for years-no bureaucracy, no billing, just a phone call and a van. It’s simple. It’s human. And it works. Why can’t we apply this everywhere? The answer isn’t more money. It’s more trust.

Naomi Walsh

The entire premise is flawed. You can't fix a broken system by rearranging deck chairs. The FDA's 'fast-track' approvals are a charade-many of these new manufacturers are subsidiaries of the same Chinese conglomerates that caused the shortages in the first place. The real solution? Nationalize the entire supply chain. Until then, this is performative reform.

Lu Gao

Wait… so you’re saying hospitals are actually *preparing*? 🤨 I thought this was a joke. You mean they’re not just waiting for the FDA to panic and then blaming China? What’s next? Doctors washing their hands? 😏

Angel Fitzpatrick

This is all a distraction. The real shortage? Truth. The FDA, Big Pharma, and hospitals are all in bed together. They let shortages happen so they can push expensive 'alternatives' that aren’t alternatives at all-just branded generics with a new label. The AI? A smoke screen. The real solution? Defund the FDA. Let the market crash. Then we’ll see who’s really in control.

June Richards

They spent $2.1 million to save $4.7 million? Wow. What a genius. Meanwhile, my hospital still uses clipboards to track inventory. This isn’t innovation. It’s luxury. And don’t get me started on the 'transparency' with patients. Most people don’t even know what a generic drug is.