When your lungs start to stiffen like old rubber, breathing becomes a battle you didn’t sign up for. Interstitial lung disease isn’t one condition-it’s a group of over 200 disorders where the tissue around your air sacs turns scarred, thick, and unyielding. This isn’t just aging. It’s progressive, often silent, and can turn simple tasks like walking to the mailbox into exhausting ordeals. The damage doesn’t heal. But it doesn’t have to keep getting worse.

What Happens Inside Your Lungs With ILD?

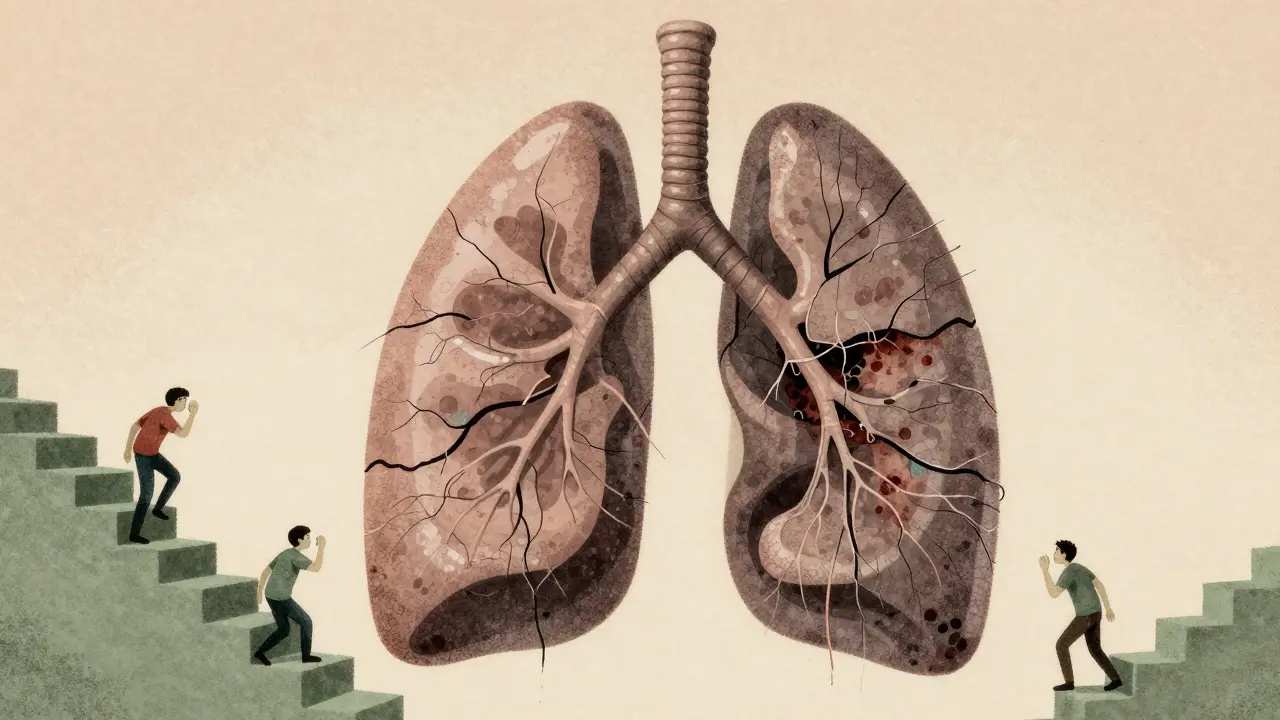

Your lungs are made of millions of tiny air sacs called alveoli. Between them is a thin layer of tissue-the interstitium. In healthy lungs, this layer is less than 0.1mm thick. In ILD, it thickens to 1mm or more from scar tissue. This isn’t inflammation you can shake off. It’s fibrosis: the body’s overzealous repair system turns normal tissue into stiff, non-functional fibrous bands.As this happens, your lungs lose their ability to expand. Oxygen can’t cross into your bloodstream as easily. That’s why the first sign is almost always shortness of breath during activity-climbing stairs, carrying groceries. Then it creeps into rest. By the time you’re breathless sitting still, the scarring is advanced. About 92% of people with ILD report this symptom, along with a dry cough that won’t quit, constant fatigue, and sometimes clubbed fingers-where fingertips swell and curve unnaturally.

Doctors measure the damage with tests like pulmonary function tests. A drop in forced vital capacity (FVC) by 20-50% or a 30-60% drop in DLCO (how well your lungs transfer oxygen) confirms moderate to severe disease. High-resolution CT scans show the scarring patterns. But here’s the catch: 20% of early ILD cases are missed because the scars are too subtle for even experienced radiologists to spot without AI assistance.

Not All ILD Is the Same

ILD isn’t a single disease. It’s a family. And each member behaves differently.Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common, making up 20-30% of cases. It has no known cause, progresses steadily, and without treatment, median survival is just 3-5 years after diagnosis. FVC declines by 200-300 mL per year in IPF-much faster than in other forms.

Connective tissue disease-associated ILD (like from rheumatoid arthritis or lupus) often moves slower. Survival rates can hit 70-80% at five years. The key? Treating the underlying autoimmune disease.

Sarcoidosis affects about 15% of ILD patients. In 60-70% of cases, it resolves on its own within two years. No treatment needed. But in others, it turns chronic and fibrotic-same end result, different path.

Drug-induced ILD can happen after taking certain antibiotics, chemotherapy drugs, or even some heart medications. The good news? Stopping the drug often halts or even reverses the damage within 3-6 months.

Asbestosis and other occupational exposures (silica, coal dust) cause slower progression-only 100-150 mL FVC loss per year. But the scars are permanent. And if you worked in construction, mining, or shipbuilding decades ago, this could be the silent price you’re paying now.

How Is It Diagnosed? And Why Does It Take So Long?

The average time from first symptom to correct diagnosis is 11.3 months. Why so long? Because symptoms look like asthma, COPD, or just “getting older.” One patient told a support forum they were misdiagnosed three times before someone finally saw the fibrosis on their CT scan.Diagnosis isn’t just one test. It’s a team effort:

- High-resolution CT scan (HRCT) with 1mm slices-this is the gold standard.

- Pulmonary function tests to measure lung volume and oxygen transfer.

- Blood tests to rule out autoimmune causes.

- 6-minute walk test to see how oxygen levels drop with activity.

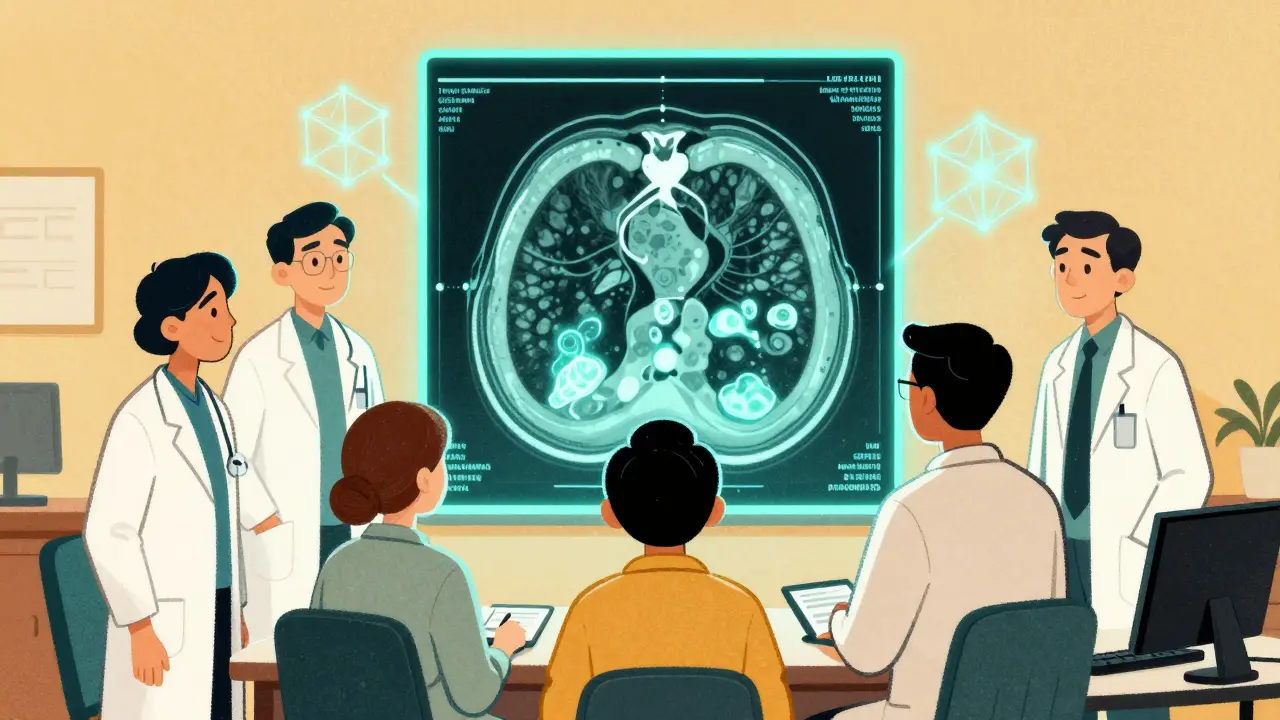

- Multidisciplinary discussion: pulmonologist, radiologist, pathologist review all data together.

Without this team approach, misdiagnosis happens in 25-30% of cases. That’s why major hospitals now have dedicated ILD clinics. Community hospitals? They’re 35% less likely to get it right.

Treatment: Slowing the Scarring, Not Reversing It

There’s no cure. But we can slow it down.For IPF, two drugs are FDA-approved and backed by years of data:

- Nintedanib (Ofev®): 150mg twice daily. Slows FVC decline by about 50% over a year.

- Pirfenidone (Esbriet®): 801mg three times daily. Same effect. But it comes with side effects-sun sensitivity (65% of users), nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.

These drugs don’t fix your lungs. They don’t make you feel better overnight. But they buy you time. In the INPULSIS trials, patients on nintedanib had half the rate of lung function loss compared to placebo.

Here’s the hard part: these drugs cost $9,450-$11,700 a month. Insurance helps, but many still face high out-of-pocket costs. Copay assistance programs exist, but navigating them takes time and support.

For non-IPF ILD, these drugs don’t work as well. Dr. Talmadge King Jr. put it bluntly: “Antifibrotics show minimal benefit outside of IPF.” That’s why research is racing toward subtype-specific treatments.

New Hope: What’s on the Horizon?

The landscape is changing fast.In September 2023, the FDA approved zampilodib, the first new antifibrotic since 2014. In the ZENITH trial, it cut FVC decline by 48% compared to placebo. It’s not for everyone yet-but it’s a sign we’re moving beyond the two old drugs.

Genetic testing is now part of the picture. The MUC5B promoter polymorphism test can predict who’s likely to have rapid IPF progression with 85% accuracy. If you test positive, your doctor might start treatment earlier.

Artificial intelligence is helping too. Mayo Clinic’s AI tool analyzed CT scans and spotted ILD subtypes with 92% accuracy-better than most human radiologists. That means faster, more precise diagnoses.

And clinical trials are exploring stem cells, new kinase inhibitors, and combination therapies. Over 25 active trials are underway as of late 2023.

Support That Actually Helps

Medications only go so far. Real improvement comes from lifestyle and support.Pulmonary rehabilitation is the most underused tool. It’s not just exercise. It’s a full program: supervised workouts, breathing techniques, nutrition advice, and energy-saving strategies. After 8-12 weeks, patients typically gain 45-60 meters on their 6-minute walk test. Seventy-two percent report better quality of life.

Oxygen therapy becomes necessary when resting oxygen saturation drops below 88%. About 55% of IPF patients need it within two years. Learning to use portable tanks or concentrators takes training-usually 3-4 sessions. But once mastered, it lets people leave the house, travel, and breathe easier.

And then there’s mental health. Sixty-eight percent of ILD patients report serious anxiety over breathlessness. Forty-five percent stop seeing friends because carrying oxygen feels isolating. Counseling, support groups, and even virtual meetups make a measurable difference.

Family caregivers are often overlooked. The Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation found that 81% of caregivers spend 20+ hours a week helping-managing oxygen, helping with mobility, coordinating appointments. That’s a full-time job on top of their own life.

What You Can Do Today

If you’ve been told you have ILD-or suspect you might:- Get a high-resolution CT scan if you haven’t already.

- Ask for a multidisciplinary evaluation-not just a pulmonologist, but a team.

- Find out if you’re eligible for antifibrotic therapy. Don’t assume you’re not.

- Start pulmonary rehab. Even if you feel too tired, the program is tailored to your limits.

- Quit smoking if you still do. It accelerates scarring.

- Get vaccinated for flu, pneumonia, and COVID-19. Infections can trigger deadly flare-ups.

- Join a support group. You’re not alone. And hearing how others manage helps more than you think.

ILD is not a death sentence. It’s a challenge-one that demands awareness, early action, and the right team. The tools to manage it are better than ever. The key is not waiting until you’re gasping for air.

Is interstitial lung disease the same as pulmonary fibrosis?

Pulmonary fibrosis is a type of interstitial lung disease (ILD), but not all ILD is fibrosis. ILD is the broader category that includes over 200 conditions. Pulmonary fibrosis refers specifically to the scarring of lung tissue. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most common form of fibrotic ILD, but other types like sarcoidosis or connective tissue disease-related ILD may involve inflammation without heavy scarring-at least at first.

Can you live a normal life with ILD?

Many people with ILD live full, meaningful lives, especially if diagnosed early and managed well. While lung function declines over time, treatments like antifibrotic drugs and pulmonary rehab can slow progression significantly. Oxygen therapy, energy conservation techniques, and avoiding triggers like smoke or pollution help maintain independence. People continue working, traveling, and spending time with family-just with adjustments.

What triggers an ILD flare-up?

Acute exacerbations-sudden worsening of symptoms-are often triggered by infections (like flu or pneumonia), environmental irritants (dust, smoke, mold), or even uncontrolled heart failure. In some cases, the cause is unknown. Avoiding crowds during cold and flu season, getting vaccinated, and using air purifiers can reduce risk. If you notice rapid increase in breathlessness, fever, or coughing up mucus, contact your doctor immediately.

Are the medications for ILD worth the side effects?

For people with IPF, yes-when weighed against the alternative. Nintedanib and pirfenidone reduce lung function decline by about half. Side effects like nausea, sun sensitivity, or fatigue are common, but most can be managed: taking pirfenidone with food reduces stomach upset, and strict sun protection prevents rashes. Many patients find the trade-off worthwhile because they can stay active longer. Your doctor can help adjust doses or switch drugs if side effects are unbearable.

How do I know if my ILD is getting worse?

Watch for these signs: needing more oxygen than before, walking slower or stopping more often during daily tasks, losing weight without trying, or having more frequent coughing fits. A drop of more than 50 meters in your 6-minute walk test over a year is a red flag. Regular pulmonary function tests every 3-6 months are the best way to track progression. Don’t wait for symptoms to feel worse-schedule your follow-ups.

Can ILD be reversed?

No, the scar tissue in ILD cannot be reversed with current treatments. That’s why early diagnosis and slowing progression are so critical. In rare cases, like drug-induced ILD, stopping the offending medication can lead to partial healing. But for IPF and most fibrotic forms, the goal is to prevent further damage-not undo what’s already there. Lung transplant remains the only option for reversal, but it’s only suitable for a small number of younger, otherwise healthy patients.

Is ILD hereditary?

Most cases aren’t inherited, but about 10-15% of IPF cases have a family history. Genetic mutations, especially in genes like MUC5B, TERC, and TERT, increase risk. If you have close relatives with ILD or unexplained lung scarring, genetic counseling and screening may be recommended. Even if you carry a risk gene, environmental factors like smoking or exposure to dust still play a major role in whether the disease develops.

What’s the difference between ILD and COPD?

COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) is mainly caused by smoking and affects the airways and air sacs, leading to airflow blockage. ILD affects the lung tissue between air sacs, causing stiffness and poor oxygen transfer. COPD patients often wheeze and produce mucus; ILD patients have dry cough and get winded easily with minimal activity. Lung function tests show different patterns: COPD has obstructive airflow, ILD has restrictive patterns. Treatments are completely different.

Next Steps If You’re Diagnosed

Start by asking your doctor for a referral to an ILD specialist center. If you’re not near one, ask for a telehealth consult. Get your HRCT reviewed by a radiologist experienced in ILD. Join a pulmonary rehab program-even if you think you’re too tired. Start tracking your symptoms: how far you walk, how much oxygen you use, your weight. Keep a journal. It helps your team adjust your care.And don’t wait for a crisis. The best outcomes come from early, consistent management-not emergency responses. ILD moves slowly-but so does progress when you act on it.

10 comments

Ryan Pagan

Man, I’ve seen this play out with my uncle-diagnosed with IPF after three years of being told it’s just ‘old age.’ He started on nintedanib last year, and while he still gets winded climbing stairs, he’s walking his grandkids to the bus stop again. That 50% slower decline? It’s not a cure, but it’s a lifeline. And pulmonary rehab? Best thing he ever did. Not because it made him strong, but because it gave him back control.

Kristie Horst

It’s staggering how often ILD is dismissed as ‘just bronchitis’ or ‘aging lungs.’ I work in a community clinic, and I’ve watched patients cycle through three different doctors before someone finally ordered an HRCT. The fact that 20% of early cases are missed without AI is not a technical gap-it’s a systemic failure. We need mandatory ILD screening protocols for anyone over 50 with persistent dry cough. Not optional. Not ‘if you’re concerned.’ Mandatory.

Alex Flores Gomez

Let’s be real-these drugs cost more than my car. Nintedanib’s $11k/month? And you’re telling me I’m supposed to be grateful it slows decline instead of reversing it? Meanwhile, Big Pharma is raking in billions while patients choose between meds and groceries. This isn’t medicine. It’s extortion with a stethoscope.

Laia Freeman

omg i just found out my mom’s dry cough is ILD… she’s been ‘just tired’ for 2 years!! i’m crying rn. but like… pulmonary rehab? is that even a thing near us?? plz help!!

Robin Keith

What fascinates me-philosophically speaking-is the irony: our bodies, evolved over millennia to heal, now turn their greatest strength-the capacity to scar-into a death sentence. Fibrosis is not disease; it is the body’s tragic misinterpretation of repair. It doesn’t want to kill you. It wants to protect you. But in its zeal, it turns your lungs into concrete. And we, the architects of modern medicine, stand there with our antifibrotics, whispering, ‘We can slow it…’ But can we ever understand why it happened? Or are we just patching the leak while the ocean rises?

rajaneesh s rajan

Bro, I’m from India, and here, most people think ‘lung problem’ = smoking. No one even knows ILD exists. My cousin had it, got misdiagnosed as asthma, died in 18 months. No CT scan. No specialist. Just inhalers and prayers. The AI tools you guys have? We’d kill for them. Meanwhile, our pulmonologists are overwhelmed, underpaid, and clueless. This isn’t a medical issue-it’s a global inequality crisis.

paul walker

Just wanted to say thanks for the post. My wife started rehab last month and she’s actually laughing again. Not because she’s cured, but because she’s not alone anymore. We didn’t know where to start. This guide? Saved us months of panic.

Andy Steenberge

Robin’s philosophical take is profound, but let’s not romanticize suffering. The real hero here isn’t the body’s misguided repair mechanism-it’s the multidisciplinary team. Radiologists who spot subtle patterns. Pulmonologists who refuse to accept ‘it’s just aging.’ Rehab specialists who tailor exercises to breathlessness. These aren’t magic bullets-they’re human beings showing up, day after day, with expertise and compassion. That’s the real treatment.

Frank Declemij

Drug-induced ILD is the most underreported form. I was on amiodarone for 18 months. No one warned me. Got diagnosed with fibrosis. Stopped the drug. Six months later, my CT scan showed 40% improvement. If your doctor prescribes a drug with known lung toxicity, ask: ‘Could this cause ILD?’ If they don’t know, find a new doctor.

LOUIS YOUANES

So we’re spending $10k a month to slow a disease that kills in 3-5 years… and the only ‘cure’ is a transplant that 90% of us aren’t eligible for? This isn’t science. It’s a pyramid scheme where the patients are the last layer.