The U.S. is facing its worst drug shortage crisis in history. As of November 2025, there are still 277 active drug shortages nationwide, according to Global Biodefense. These aren’t just minor inconveniences-they’re life-or-death gaps in care. Cancer patients miss chemotherapy doses. Hospital ERs scramble for antibiotics. Anesthesiologists delay surgeries because the only available IV bag is from a different manufacturer with untested side effects. The federal government has responded with new policies, but the results are mixed, and many of the root problems remain untouched.

What’s Really Causing These Shortages?

It’s not one thing. It’s a chain of failures. Most critical drugs-especially sterile injectables like saline, insulin, and chemotherapy agents-are made in just a handful of factories. Three companies control nearly 70% of the U.S. sterile injectable market. If one plant shuts down for a quality issue, the entire country feels it. Over 80% of the raw ingredients (active pharmaceutical ingredients, or APIs) come from China and India. These suppliers aren’t just far away-they’re often the only source. No backup. No redundancy. Manufacturers don’t make money on these drugs. A vial of generic doxycycline might cost $0.50 to produce but sells for $1.25. Compare that to a new cancer drug that costs $10,000 a dose. Why would a company invest millions to build a second production line for a drug that barely covers its costs? The market punishes competition in low-margin essential medicines. So they don’t. And when something goes wrong-power outage, contamination, equipment failure-the system has no cushion.The Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve (SAPIR)

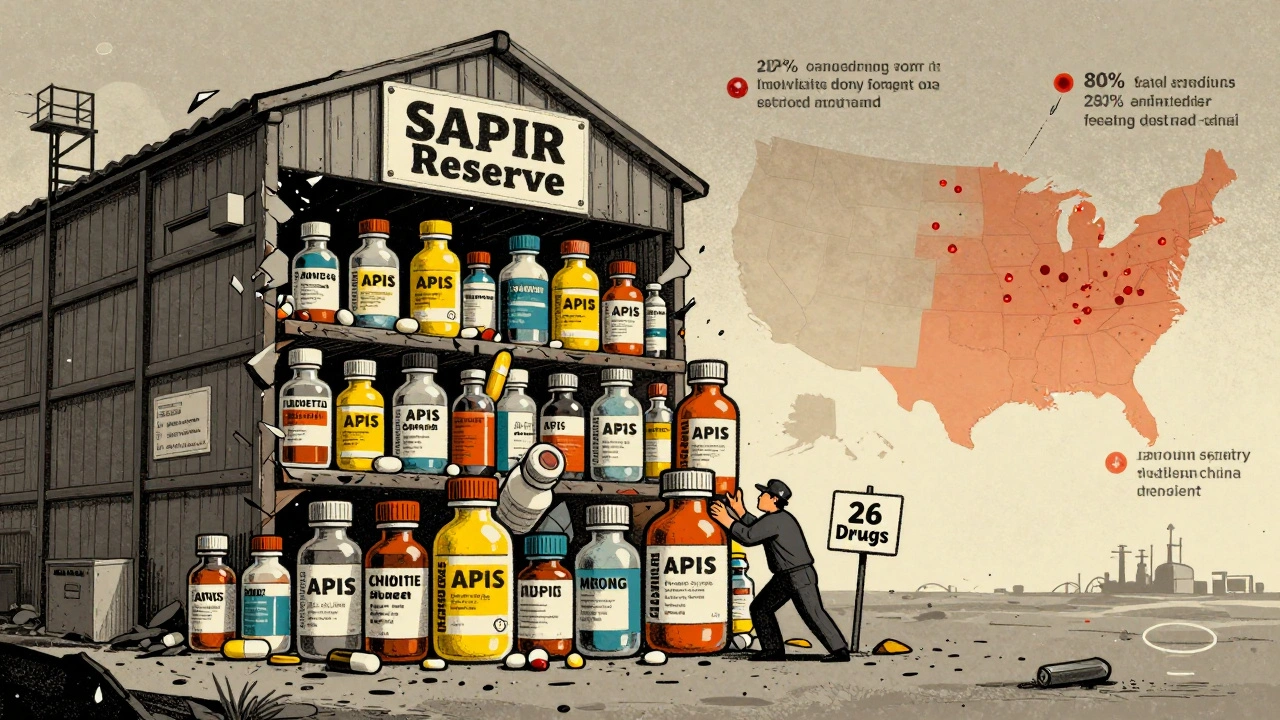

In August 2025, President Trump signed Executive Order 14178, expanding the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve (SAPIR). This program now stockpiles raw ingredients for 26 essential drugs: antibiotics, anesthetics, and key oncology medications. The idea? APIs last 3 to 5 years longer than finished drugs and cost 40-60% less to store. Instead of hoarding vials of epinephrine, the government hoards the chemical that makes epinephrine. The theory sounds smart. But here’s the catch: only 12% of critical API production has been brought back to the U.S. in seven years of federal efforts. The SAPIR reserve doesn’t fix manufacturing. It just delays the crisis. And it’s narrow. The 26 drugs on the list make up less than 5% of all shortage incidents. The FDA’s own data shows that oncology drugs alone account for 31% of all shortages-but only 4% of the SAPIR list.FDA’s Role: Enforcement vs. Flexibility

The FDA has two jobs: keep drugs safe and keep them available. They’ve tried both. In 2024, they resolved 85% of shortages by working directly with manufacturers-fast-tracking inspections, allowing temporary imports, and giving companies extra time to fix problems. That’s how they solved the saline shortage that hit 90% of U.S. hospitals in 2018. But enforcement? That’s weak. Between 2020 and 2024, the FDA issued only 17 warning letters for companies that failed to report potential shortages-even though the law requires it. The European Union issued 142 under similar rules. In the U.S., reporting is voluntary in practice. Only 58% of manufacturers comply with the six-month advance notice rule. Small companies? Only 18% report on time. In November 2025, the FDA launched its Enhanced Shortage Monitoring System. It uses AI to track 17 data streams: shipping delays, hospital purchase patterns, factory batch records. It predicts shortages 90 days in advance with 82% accuracy. That’s a big step. But if no one’s required to report early, the system only sees what’s already broken.

What Congress Is Trying to Fix

H.R.5316, the Drug Shortage Act, is moving through the 119th Congress. It would let pharmacists compound urgent-use medications without waiting for full FDA approval. That’s helpful for hospitals running out of rare drugs. It also creates a new fund to help hospitals maintain backup suppliers. The Congressional Budget Office estimates it could cut shortages by 15-20% over five years-for $740 million. That’s less than 0.1% of total U.S. drug spending. The bipartisan Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Act proposes something even more practical: Medicare bonus payments to hospitals that keep alternative drug sources on hand. Right now, hospitals spend an average of $1.2 million a year just managing shortages-tracking inventory, switching meds, training staff, dealing with errors. If Medicare rewarded them for being prepared, more would do it. But neither bill tackles the real problem: low profit margins. Without financial incentives to make generic drugs, nothing changes.The Bigger Picture: Why Stockpiling Isn’t Enough

Dr. Luciana Borio, former FDA Acting Chief Scientist, put it bluntly in her September 2025 commentary: “The U.S. approach is reactive, not preventative.” Stockpiling APIs helps in a crisis. But it doesn’t stop the next crisis. The real fix is building more factories-here, in the U.S.-and making it worth the cost. The Department of Commerce gave $285 million in CHIPS Act funding to support domestic drug manufacturing in September 2025. Sounds good. But experts say it takes $6 billion to make a real difference. That’s less than 5% of what’s needed. Even when companies try to build here, they’re slowed down. FDA approval for a new API plant takes 28-36 months. In the EU, it takes 18-24. Why? More inspections. More paperwork. Less coordination. The FDA isn’t broken-it’s overloaded.

Who’s Paying the Price?

Hospitals aren’t just spending money-they’re risking lives. A 2025 American Hospital Association survey found that 68% of hospitals have delayed treatments because of shortages. 42% reported medication errors from switching drugs. Pharmacists spend 10+ hours a week just managing inventory. On Reddit, one pharmacist wrote: “I had to compound cisplatin from raw powder because the vial was gone. We had no choice.” Patients are skipping doses. A September 2025 report from Patients for Affordable Drugs found 29% of Americans skipped medication due to unavailability-not because they couldn’t afford it, but because it simply wasn’t in stock. Cancer patients were hit hardest: 68% had their treatment changed, delayed, or reduced.What’s Working? What’s Not

The only federal initiative with proven results is the FDA’s Early Notification Pilot Program. Hospitals that reported potential shortages early saw their shortage durations drop by 28%. Mandatory reporting works. But the current administration has weakened those rules. The FDA now accepts voluntary reports. That’s like asking firefighters to call in fires when they feel like it. The EU’s approach is simpler: require member states to stockpile critical drugs and create a centralized monitoring system. Between 2022 and 2024, their shortages dropped by 37%. They didn’t wait for a crisis. They planned for it. The U.S. is trying to do both: stockpile and fix manufacturing. But without funding, without enforcement, and without a clear plan to make low-margin drugs profitable, it’s like patching a sinking ship with duct tape.What Comes Next?

By Q2 2026, 14 new applications for second-source manufacturers are in review by the FDA. If approved, they could add backup supply for eight critical drugs. That’s progress. But it’s slow. And it’s not enough. The real test will be in 2027. Will the SAPIR reserve be fully stocked? Will hospitals get paid to prepare? Will Congress fund domestic manufacturing at the scale needed? Or will we keep patching the same holes, year after year, while patients suffer? Until the government makes it profitable to make essential drugs here, and until it forces manufacturers to report problems before they become crises, drug shortages will keep happening. Not because of bad luck. Because of bad policy.Why are drug shortages getting worse despite federal efforts?

Because most federal actions focus on reacting to shortages, not preventing them. Stockpiling raw ingredients helps in emergencies, but it doesn’t fix the root causes: too few manufacturers, no financial incentive to make low-profit drugs, and weak enforcement of reporting rules. Over 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients still come from overseas, and 78% of sterile injectable production is concentrated in just five U.S. facilities. Without addressing these structural issues, shortages will keep rising.

What is the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve (SAPIR)?

SAPIR is a federal stockpile of raw chemical ingredients (APIs) for 26 essential drugs like antibiotics, anesthetics, and cancer medications. Launched in 2020 and expanded in August 2025, it aims to reduce dependence on foreign suppliers by storing cheaper, longer-lasting ingredients instead of finished drugs. The goal is to quickly produce medications during shortages. But it only covers a small fraction of the drugs in crisis, and it doesn’t increase domestic production capacity.

How does the FDA currently handle drug shortages?

The FDA works directly with manufacturers to resolve 85% of shortages by offering regulatory flexibility-like fast-tracking inspections or allowing temporary imports. They also launched an AI-powered monitoring system in November 2025 that predicts shortages 90 days in advance with 82% accuracy. But enforcement is weak: only 17 warning letters were issued between 2020-2024 for failing to report shortages, despite legal requirements. Reporting is mostly voluntary, and compliance is below 60%.

Are there any laws being proposed to fix drug shortages?

Yes. H.R.5316, the Drug Shortage Act, would allow pharmacists to compound urgent-use drugs faster and fund backup supply chains. Another bill, the Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Act, would give Medicare bonuses to hospitals that maintain alternative drug sources. Both aim to reduce shortages by 15-20%, but critics say they don’t tackle the core problem: manufacturers lose money making essential generic drugs. Without changing how these drugs are paid for, the fixes won’t last.

How do drug shortages affect patients?

Patients are skipping doses, delaying treatments, or getting substituted medications with unknown side effects. A 2025 survey found 29% of Americans skipped medication due to unavailability-not cost. Cancer patients were hit hardest: 68% had treatment changes. Hospitals report increased medication errors, longer wait times, and extra clinical monitoring. Pharmacists spend over 10 hours a week just tracking down drugs. These aren’t administrative problems-they’re patient safety crises.

Why isn’t the U.S. making more drugs domestically?

Because it’s not profitable. Generic drugs have razor-thin margins, and building a new FDA-approved manufacturing plant takes 28-36 months and millions in investment. Companies prefer to make high-profit drugs or outsource production overseas where labor and regulation are cheaper. Even with $285 million in federal funding, that’s less than 5% of what’s needed to build enough domestic capacity. Without financial incentives or guaranteed demand, manufacturers won’t risk it.

14 comments

Chris Wallace

It’s wild how we treat life-saving meds like they’re just another commodity. I’ve seen pharmacists crying in the back room because they had to give a kid a different antibiotic that might not work as well. And nobody’s talking about how this isn’t just a supply chain issue-it’s a moral failure. We let companies make billions on cancer drugs while generic injectables get ignored. And now we’re surprised when people die because a vial didn’t arrive on time? We built a system that rewards greed and punishes compassion. It’s not broken. It’s working exactly as designed.

Eddy Kimani

From a pharma ops standpoint, the SAPIR initiative is a clever band-aid on a hemorrhaging artery. APIs have longer shelf lives, yes-but without GMP-compliant domestic manufacturing capacity, you’re just moving the bottleneck upstream. The real KPI we should be tracking isn’t stockpile volume-it’s lead time variance for sterile injectables. And the data shows it’s getting worse. AI monitoring is great, but if the upstream data inputs are voluntary and 42% incomplete, your predictive model is just noise with confidence intervals. We need mandatory real-time ERP integration from all manufacturers. Period.

Chelsea Moore

This is UNACCEPTABLE!!! How DARE they let people die because some CEO decided it was ‘not profitable’ to make saline?!?!? We’re talking about LIFE-OR-DEATH DRUGS here!!! And the FDA? Just sitting there with their hands in their pockets like it’s a traffic ticket!!! I’m SO done with this system!!! 😭💔 #FixItNow #NoMoreExcuses

John Biesecker

man i just keep thinking about how we’d react if this was about toilet paper or chicken nuggets. imagine if every hospital ran out of toilet paper for 3 months and people started getting infections because they had to reuse wipes. we’d riot. we’d burn down the factories. but when it’s medicine? we just sigh and say ‘oh well, capitalism.’ 🤷♂️ maybe we need a new economic model. one where life isn’t priced by profit margins. i don’t know. but this feels wrong. like, deeply wrong. 😔

Genesis Rubi

China and India are laughing all the way to the bank while our kids get delayed chemo. We let our entire pharma supply chain get outsourced to dictators and corrupt regimes. And now we’re surprised? Pathetic. We need to shut down every foreign API plant that ships to us. Build our own. Nationalize the damn factories. This isn’t about ‘free markets’-it’s about national security. And we’re losing. Wake up, America.

Doug Hawk

the data on reporting compliance is terrifying. 58% of manufacturers don’t even tell the fda when they might run out? that’s like a pilot not telling air traffic control their fuel is low. the fda’s ai system is brilliant but it’s trying to predict crashes from smoke after the fire’s already started. mandatory reporting with real penalties-like license suspension or fines tied to revenue-would force change. no more ‘oops we forgot.’ this isn’t a suggestion box. it’s a public health emergency.

Michael Campbell

The FDA’s AI system? Probably funded by Big Pharma. They want you to think tech will fix this. It won’t. The real plan? Let people die quietly so they can push through a national drug monopoly. Watch. They’ll say ‘we need one supplier to control quality.’ Then they’ll raise prices 1000%. This is all a setup.

Victoria Graci

it’s funny how we call these ‘shortages’ like they’re accidents. they’re not. they’re engineered. the profit structure is designed to make low-margin generics unviable. it’s not ‘market failure’-it’s market design. we’ve turned medicine into a casino where the house always wins, and the patients are the ones losing their chips. if we treated oxygen like this-‘well, it’s too expensive to produce so we ration it’-we’d be in the streets. but because it’s pills and vials, we just scroll past. we’ve normalized suffering.

Saravanan Sathyanandha

As someone from India, I see the irony. Our factories churn out 40% of the world’s generic drugs, yet we lack the infrastructure to supply our own rural clinics reliably. The U.S. blames outsourcing, but the truth is, global pharma is a web of interdependence. The real solution isn’t isolation-it’s cooperation. Invest in Indian and Chinese GMP upgrades, not just U.S. stockpiles. Create a global API consortium with shared quality standards. It’s cheaper, faster, and more ethical than playing nationalistic tug-of-war.

alaa ismail

i just think about how many people are sitting in ERs right now waiting for a vial that’s sitting in a warehouse in shanghai. and we’re arguing about funding. it’s so weird how we can spend trillions on war but can’t afford to keep someone alive for 30 days. just food for thought.

ruiqing Jane

Let’s be clear: hospitals are doing heroic work under impossible conditions. But the system is failing them. Medicare bonuses for maintaining backup suppliers? Brilliant. Why? Because it aligns incentives with outcomes. Right now, hospitals are punished for being prepared-they get reimbursed for treating patients, not preventing crises. This bill doesn’t fix everything, but it’s the first policy I’ve seen that doesn’t treat healthcare workers like disposable parts. We need more of this.

Fern Marder

The EU dropped shortages by 37%? Yeah, because they have socialized medicine. We don’t. We’re a capitalist nightmare with a side of denial. 🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸 The FDA’s ‘flexibility’ is just letting companies drag their feet. Mandatory reporting? Too much ‘government overreach.’ SAPIR? Cute. But we’re not fixing the root cause: profit > people. We’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. 🚢💀

Carolyn Woodard

the statistical disconnect between the 26 drugs in sapi and the 31% of shortages from oncology meds is staggering. it’s not just a gap-it’s a chasm. why are we prioritizing anesthetics over chemo? because they’re cheaper to stockpile? because they’re used in elective procedures? this isn’t risk-based-it’s politically expedient. the fda’s own data is being weaponized to justify inaction. if you’re going to build a reserve, build it around the drugs that kill people when they’re gone. not the ones that inconvenience surgeons.

Allan maniero

I’ve spent the last decade working in NHS logistics, and I can tell you this: the U.S. is trying to solve a systemic problem with tactical fixes. The EU model isn’t perfect, but their centralized procurement and mandatory buffer stock policies have real teeth. Here, we have 12,000 hospitals each doing their own inventory dance. No coordination. No leverage. No accountability. And now we’re surprised that when one plant in New Jersey shuts down, a hospital in rural Montana can’t get saline? We need a national drug supply authority-not another pilot program. A single entity with real power to mandate, fund, and enforce. Otherwise, we’re just rehearsing the same tragedy, scene after scene.