DVT & Heart Disease Risk Calculator

This tool helps you understand how your lifestyle and health factors impact your risk for both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and heart disease. These conditions share many risk factors, so reducing your risk for one often benefits the other.

Your Risk Assessment

Your risk assessment shows low potential for both conditions. Consider maintaining your current healthy habits.

Quick Takeaways

- Both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and heart disease share lifestyle and genetic risk factors.

- A clot that starts in the leg can travel to the lungs, raising heart strain and triggering arterial inflammation.

- Blood tests such as D‑dimer and imaging like ultrasound help catch problems early for both conditions.

- Anticoagulants, regular movement, and a heart‑healthy diet lower the odds of developing either problem.

- Understanding the overlap lets patients and clinicians act sooner, reducing complications.

When you hear "deep vein thrombosis" you probably picture a painful, swollen calf. When you think of "heart disease" you imagine a blocked artery. They seem like separate worlds-one in the veins of your legs, the other in the arteries of your heart. Yet doctors have spotted a clear connection: clot‑forming tendencies, inflammation, and shared lifestyle culprits tie the two together. This guide walks through what each condition is, why they overlap, and what you can do to protect both.

What is Deep Vein Thrombosis?

DVT is a blood clot that forms in the deep veins, most often in the thighs or calves. The clot can partially or fully block blood flow, causing pain, swelling, and sometimes a warm, reddish skin tone. If a piece of the clot breaks off, it may travel through the bloodstream and become a pulmonary embolism (PE), a life‑threatening blockage in the lungs.

Key attributes of DVT include:

- Location: Deep veins of the lower extremities.

- Typical symptoms: Leg pain, swelling, redness, and a feeling of heaviness.

- Major triggers: Immobility (long flights, surgery), hypercoagulability (genetic clotting disorders), and venous stasis.

What is Heart Disease?

Heart disease is an umbrella term covering conditions that affect the heart's ability to pump blood effectively. The most common form is coronary artery disease (CAD), where plaque builds up in the arteries that feed the heart muscle, narrowing or blocking flow. Over time, reduced blood supply can cause chest pain (angina), heart attacks, or heart failure.

Important characteristics:

- Primary sites: Coronary arteries, heart valves, and the cardiac muscle itself.

- Symptoms: Chest discomfort, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations.

- Risk contributors: High blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, sedentary lifestyle.

Shared Risk Factors

Both DVT and heart disease thrive on similar conditions. Knowing these overlaps helps you attack the problem from both ends.

- Immobility: Long car trips, post‑surgical bed rest, or desk‑bound work can slow blood flow in veins and add stress to the heart.

- Obesity: Excess weight raises pressure in leg veins and worsens cholesterol and blood pressure, feeding arterial plaque.

- Smoking: Nicotine thickens blood, damages vessel walls, and promotes clot formation.

- Diabetes: High glucose damages both venous and arterial lining, making clots more likely.

- Genetic clotting disorders: Factor V Leiden or prothrombin mutations increase DVT risk and have been linked to earlier onset of CAD.

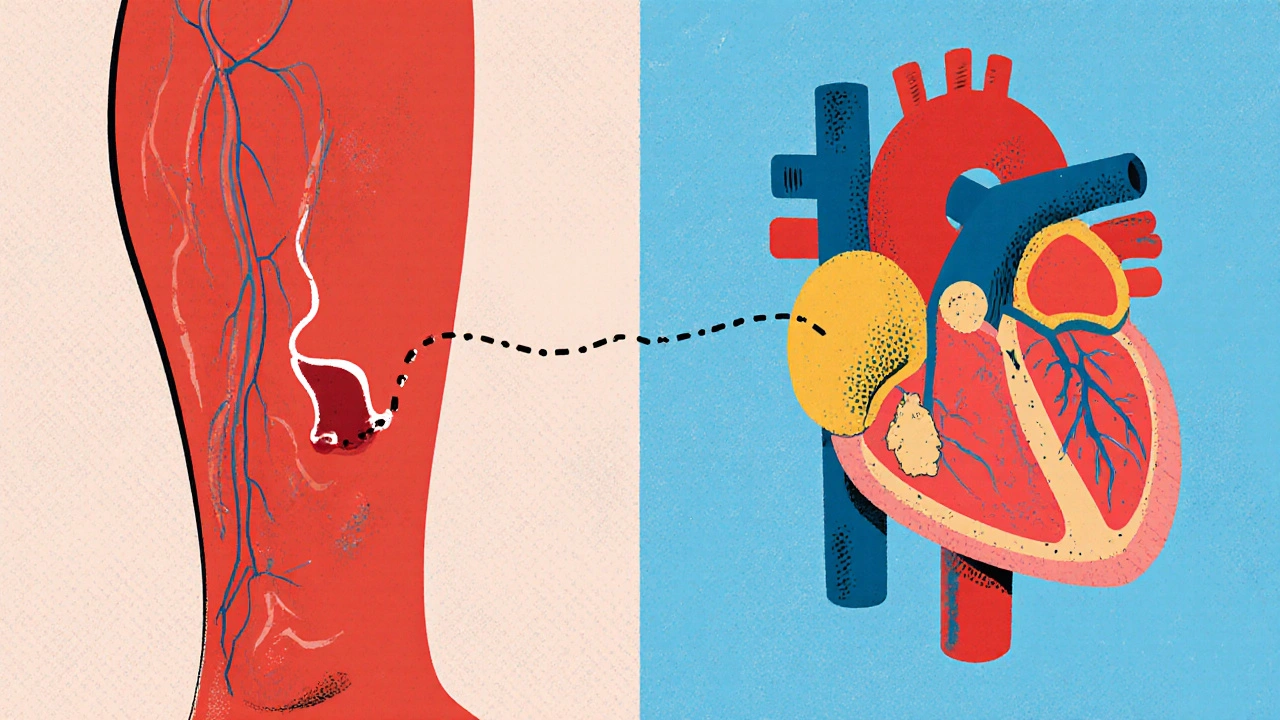

Biological Link: How Clots Affect the Heart

When a clot from a leg travels to the lungs (PE), the sudden blockage raises pulmonary artery pressure. The right side of the heart must pump harder, which can lead to right‑ventricular strain and, over time, right‑heart failure. Even smaller, sub‑clinical emboli stimulate systemic inflammation - a known driver of atherosclerosis.

Inflammatory markers released during clot formation (e.g., interleukin‑6, CRP) also accelerate plaque buildup in coronary arteries. In short, a clot in a vein can set off a chain reaction that harms the arteries feeding the heart.

Diagnostic Overlap: Tests That Catch Both

Because the two conditions share pathways, several tests can reveal clues for both.

- D‑dimer: Elevated levels suggest active clot breakdown. While not specific, a high D‑dimer can prompt imaging for DVT and also flag patients at higher risk for cardiovascular events.

- Ultrasound (venous Doppler): Detects clots in leg veins. In patients with unexplained shortness of breath, a negative leg ultrasound may push clinicians to look for cardiac sources.

- CT Pulmonary Angiography: Gold standard for PE, but it also visualizes coronary calcium scores that predict heart disease.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): A sudden PE can cause right‑axis deviation or S1Q3T3 pattern-signs that overlap with right‑heart strain from chronic heart disease.

Prevention Strategies that Benefit Both Conditions

Targeting the shared roots can lower the odds of a clot forming in your leg and the chances of arterial plaque narrowing your heart’s highways.

- Move every hour: Simple leg‑raises, short walks, or calf‑pumps keep venous blood flowing.

- Heart‑healthy diet: Plenty of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and omega‑3 fatty acids reduce inflammation and improve lipid profiles.

- Maintain a healthy weight: Even a 5‑% weight loss can drop both DVT and CAD risk.

- Quit smoking: The benefits appear within weeks for blood viscosity and continue for years for arterial health.

- Compression stockings: Graduated compression improves venous return, especially after surgery or during long travel.

- Appropriate anticoagulation: For high‑risk patients, low‑dose aspirin, warfarin, or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) protect veins without dramatically raising heart bleeding risk when monitored.

Management: Treating DVT Without Harming the Heart

When a DVT is diagnosed, doctors weigh clot‑preventing drugs against potential cardiac side effects.

| Medication | Mechanism | Heart‑Related Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | Vitamin K antagonist | Requires INR monitoring; can interact with statins and antihypertensives. |

| Apixaban (Eliquis) | Factor Xa inhibitor | Lower bleeding risk; minimal impact on blood pressure. |

| Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) | Factor Xa inhibitor | Convenient dosing; watch for occasional hypertension spikes. |

| Dabigatran (Pradaxa) | Direct thrombin inhibitor | Renal clearance - adjust for patients with heart‑failure‑related kidney issues. |

Choosing the right drug often hinges on a patient’s existing cardiac meds, kidney function, and ability to attend regular lab visits. For many, a DOAC offers a balance of clot protection and heart safety.

Quick Reference: Risk Factor Comparison

| Risk Factor | Impact on DVT | Impact on Heart Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Immobility | Stagnant venous flow → clot | Reduced cardiac output, promotes atherosclerosis |

| Obesity | Increased intra‑abdominal pressure → venous stasis | Elevated LDL, hypertension, insulin resistance |

| Smoking | Blood hypercoagulability | Endothelial damage, plaque formation |

| Genetic clotting disorders | Higher baseline clot tendency | Associated with earlier CAD onset |

| Inflammation (CRP ↑) | Promotes fibrin formation | Accelerates atherosclerotic plaque growth |

Putting It All Together

Understanding that a clot in your leg isn’t an isolated event changes how you approach health. Regular movement, a balanced diet, and smart medication choices protect both the veins and the arteries. If you’ve experienced a DVT, ask your provider about a heart‑health check‑up; if you have heart disease, discuss clot‑prevention strategies that fit your lifestyle.

Can a deep vein clot cause a heart attack?

A clot itself doesn’t block coronary arteries, but a pulmonary embolism can strain the heart and trigger arrhythmias that increase heart‑attack risk. Additionally, the inflammation from clot formation can speed up atherosclerosis, indirectly raising heart‑attack chances.

If I’m on blood thinners for DVT, will they protect my heart?

Blood thinners mainly target venous clots. They don’t dissolve arterial plaque, but they do lower the chance of a clot traveling to the lungs, which eases heart‑strain. For true heart protection, you still need statins, aspirin (if advised), and lifestyle changes.

Is a high D‑dimer level a red flag for heart disease?

Elevated D‑dimer signals active clot breakdown, which can be due to DVT, PE, or widespread inflammation. While it’s not a direct heart‑disease marker, many cardiology clinics use it as part of a broader risk assessment because inflammation links both conditions.

Do compression stockings lower heart‑disease risk?

They primarily aid venous return, cutting DVT risk. By keeping the legs moving, they reduce the overall inflammatory load, which can modestly benefit heart health, especially in sedentary individuals.

What lifestyle changes give the biggest bang for the buck?

Aim for three daily habits: 1) Move for at least 5 minutes every hour; 2) Follow a Mediterranean‑style diet rich in fish, nuts, and olive oil; 3) Quit smoking and keep weight in a healthy range. Those three hit the core risk factors for both DVT and heart disease.

10 comments

Catherine Viola

The relationship between deep vein thrombosis and coronary pathology has been scrutinized for decades by the medical establishment.

Contemporary evidence indicates that the coagulation cascade, when dysregulated, exerts systemic effects beyond the venous compartment.

In particular, elevated fibrinogen and platelet activation create a pro‑inflammatory milieu that accelerates atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Moreover, epidemiological studies reveal that individuals with inherited thrombophilias, such as Factor V Leiden, exhibit a statistically significant earlier onset of myocardial infarction.

This correlation cannot be dismissed as mere coincidence, especially when genetic predisposition simultaneously influences both venous and arterial thrombotic pathways.

It is further noteworthy that the pharmaceutical industry, motivated by profit, often obscures the intertwined nature of these conditions to market anticoagulants as solely ‘venous’ therapies.

Consequently, patients are inadequately warned about the cardiovascular ramifications of long‑term anticoagulation neglecting the necessity for concurrent lipid‑lowering strategies.

Clinical guidelines, crafted by committees with vested interests, rarely mandate a simultaneous cardiovascular risk assessment for patients presenting with DVT.

As a result, a substantial subset of DVT sufferers progress to right‑ventricular strain and subsequent heart failure without appropriate surveillance.

Preventative measures, such as regular ambulation and adherence to a Mediterranean diet, have demonstrable benefits in attenuating both clot formation and arterial plaque burden.

The mechanistic bridge is further reinforced by inflammatory cytokines, notably interleukin‑6, which is secreted during thrombus resolution and contributes to endothelial dysfunction.

Endothelial dysfunction, in turn, is the cornerstone of atherogenesis, creating a feedback loop that jeopardizes cardiac health.

Therefore, a comprehensive therapeutic approach must incorporate anticoagulation, anti‑inflammatory agents, and statin therapy to break this vicious cycle.

Patients should also be educated about the importance of compression therapy, not merely as a DVT prophylactic but as a tool to reduce venous stasis‑induced systemic inflammation.

Ignoring this holistic perspective perpetuates a fragmented healthcare model that benefits neither the patient nor public health.

In summary, recognising the pathophysiological convergence of DVT and heart disease is essential for effective prevention, early detection, and integrated management.

sravya rudraraju

Friends, the synergy between venous clots and cardiac disease is a golden opportunity for proactive health stewardship.

By embracing movement breaks every hour, we ignite venous return and simultaneously reduce shear stress on arterial walls.

Adopting a Mediterranean‑style diet, replete with omega‑3 rich fish, nuts, and olive oil, fuels anti‑inflammatory pathways that thwart both thrombosis and atherosclerosis.

Remember, consistency is the catalyst: a five‑minute walking interval repeated throughout the day compounds into a protective cascade for the heart and legs.

Let us each commit to these evidence‑based habits, empowering ourselves and those around us to defy the twin threats of DVT and coronary artery disease.

Ben Bathgate

Look, the article throws a lot of buzzwords at us but forgets to mention that most of this stuff is just textbook fluff.

If you’re already on anticoagulants, you’re not magically shielded from heart attacks – you still need the whole cardio‑pipeline.

Ankitpgujjar Poswal

Alright, listen up: if you’ve had a DVT, start a simple home‑workout routine right now – 10 calf raises every hour, no excuses.

Combine that with a heart‑healthy plate and you’re attacking the problem from both ends.

Don’t wait for the next doctor’s appointment; the time to act is this very moment.

Jay Kay

This article is a melodramatic waste of time.

Jameson The Owl

There is a hidden agenda behind the push for anticoagulants they are not telling you about the long term heart implications.

The data quietly shows higher rates of cardiac events in patients on prolonged therapy.

We should demand transparency from the medical establishment and pharmaceutical lobbyists.

Ignorance is not bliss when your heart is at stake.

Rakhi Kasana

While the guide lists useful tips, it glosses over the fact that not everyone can afford compression stockings or frequent labs.

Those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds may struggle to implement the recommendations despite best intentions.

A realistic approach must address accessibility alongside medical advice.

Sarah Unrath

i think the article could use more petar but also less boring text it is good but maybe a few typos would make it realer.

James Dean

Movement is the silent cure the heart and veins agree.

Monika Bozkurt

From a pathophysiological perspective, the interplay between venous thromboembolism and coronary artery disease exemplifies a shared endothelial dysfunction paradigm.

Integrating antithrombotic stewardship with lipid‑modulating regimens optimizes vascular homeostasis.

Healthcare providers should adopt a multidisciplinary framework that synergizes cardiology, hematology, and lifestyle medicine.

Such an evidence‑driven strategy will mitigate morbidity and enhance patient‑centered outcomes.