Did you know that combining two common sleep aids can cut a person's breathing rate in half? That statistic isn’t fiction - it’s a real, documented outcome of sedative drug interactions. When multiple central nervous system (CNS) depressants hit the brain at once, the effect is more than just the sum of its parts. The result can be rapid loss of consciousness, dangerous respiratory failure, and even death.

What are CNS depressants and how do they work?

When you hear the term CNS depressants are a class of drugs that slow down brain activity by boosting the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma‑aminobutyric acid). This slowdown reduces arousal, causes drowsiness, and relaxes muscles. The group includes several familiar substances:

- benzodiazepines - such as alprazolam and diazepam, prescribed for anxiety or insomnia.

- opioids - painkillers like oxycodone and hydrocodone that also depress breathing.

- alcohol - a legal depressant that many people use socially.

- barbiturates - older sleep aids that have largely been replaced but are still present in some prescriptions.

- sleep medications - non‑benzodiazepine agents like zolpidem that target the same GABA pathway.

Each of these drugs individually lowers the brain’s firing rate, but when taken together they pile onto the same GABA receptors, creating an additive or even synergistic effect.

Why mixing sedatives is more than just “more of the same”

Research shows that combined use leads to a phenomenon called cumulative CNS depression. In practice this means a patient’s blood pressure might drop 15‑25 mmHg, heart rate could slow by 10‑20 bpm, and breathing may fall to 8‑10 breaths per minute - half the normal adult rate. A study from the Addiction Center (2023) reported that 68% of emergency department visits involving polypharmacy featured confusion, dilated pupils, and severe drowsiness.

The most terrifying outcome is respiratory depression. When oxygen saturation slips below 90 % for just 4‑6 minutes, brain cells start to die, leading to permanent damage, seizures, coma, or death. The Cleveland Clinic (2023) measured that dangerous combos can push the respiratory rate down to 4‑6 breaths per minute, a level that forces oxygen levels under 85 % within 15‑20 minutes.

High‑risk combos and the numbers behind them

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a 2016 safety communication that identified the opioid‑benzodiazepine pair as a lethal duo. Data indicate a 2.5‑ to 4.5‑fold increase in overdose death compared with opioids alone. Below is a quick snapshot of the most hazardous pairings, based on peer‑reviewed studies:

| Combination | Risk increase (vs. single drug) | Typical respiratory rate (breaths/min) |

|---|---|---|

| Opioid + Benzodiazepine | 2.5‑4.5× overdose death | 4‑6 |

| Opioid + Alcohol | 3.0× emergency visits | 5‑8 |

| Benzodiazepine + Barbiturate | 2.0× severe sedation | 6‑9 |

| Sleep med (zolpidem) + Alcohol | 1.8× falls in elderly | 7‑10 |

These figures are not abstract - they translate to real‑world tragedies. In a cohort of 1,848 chronic opioid users, 29% without a prior substance‑use disorder (SUD) also took a sedative, and the rate climbed to 39% among those with an SUD history.

Who is most at risk?

Elderly patients experience amplified effects because liver metabolism and kidney clearance slow with age. Studies show that older adults on three or more CNS depressants have a 2.8‑fold higher fall risk and a 3.4‑fold increase in hip fractures. Female gender, depression diagnosis, and high opioid doses (≥100 morphine‑milligram equivalents per day) also predict dangerous co‑use. The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria lists 34 CNS‑active drugs that should be avoided in seniors, yet real‑world prescribing often ignores these warnings.

Beyond age, people with chronic pain, anxiety disorders, or a history of addiction are prime candidates for polypharmacy. A longitudinal study in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (2009) linked high‑dose, multi‑drug regimens to a 27 % rise in clinically important cognitive decline (a 5‑point drop on the Modified Mini‑Mental State Examination).

Spotting the warning signs

Recognizing early symptoms can buy critical minutes before an emergency. Look for:

- Severe drowsiness that does not improve with rest

- Slurred speech or confusion

- Unsteady gait or sudden stumbling

- Blue‑tinged lips or fingernails (sign of hypoxia)

- Heart rate < 60 bpm and blood pressure dropping more than 20 mmHg

If any of these appear after taking more than one depressant, call emergency services immediately. While waiting, place the person on their side (recovery position) and ensure the airway stays open.

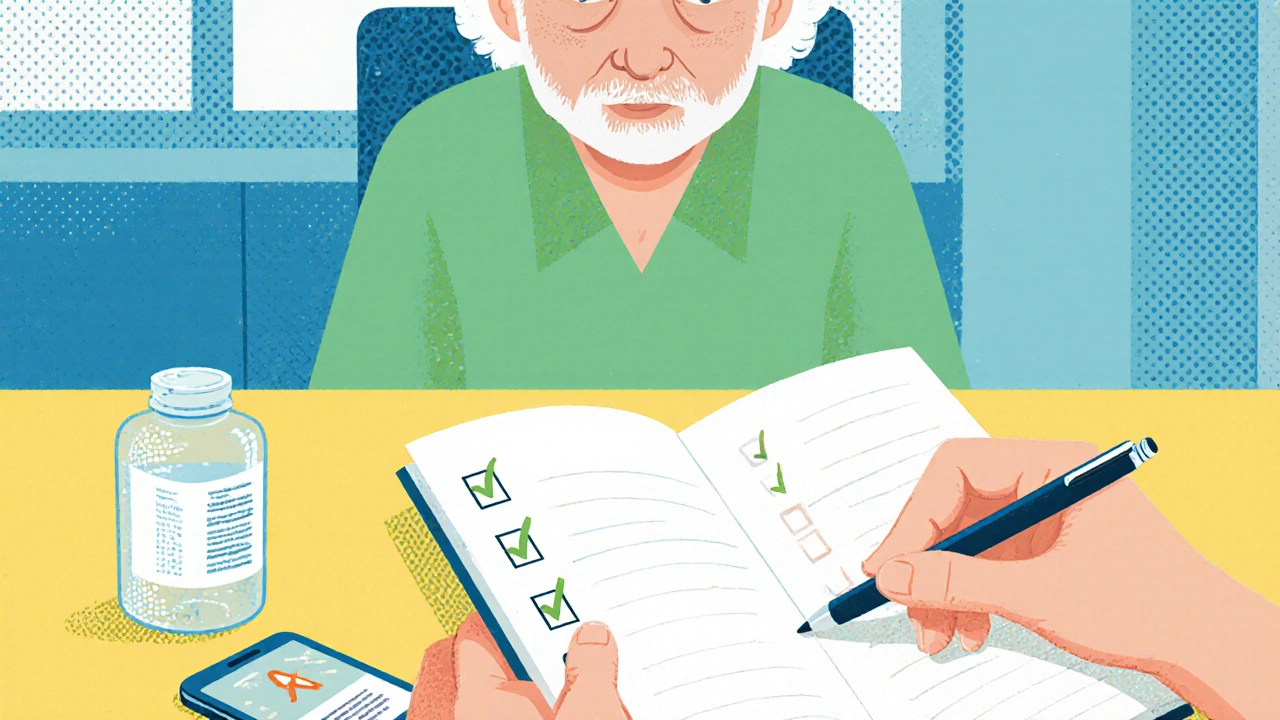

How clinicians reduce the danger

Evidence‑based strategies focus on three pillars: medication review, deprescribing, and patient education.

Regular medication reviews every 3‑6 months can catch risky combinations early. A 2023 CDS study showed that systematic reviews cut fall risk by 32 % and cognitive decline by 27 % within a year.

Deprescribing - the planned tapering or stopping of unnecessary drugs - is especially effective for long‑acting benzodiazepines. Switching to non‑benzodiazepine alternatives trimmed emergency department visits by 19 % in older adults.

Education programs that explain the hazards of polypharmacy improve medication adherence by 23 % and lower dangerous combos by 31 % when consistently delivered.

Clinical decision‑support (CDS) tools embedded in electronic health records now flag high‑risk pairings. Pilot sites report a 28 % reduction in inappropriate CNS polypharmacy after full implementation.

Regulatory moves and what’s on the horizon

The FDA’s 2016 boxed‑warning mandate forced manufacturers to print explicit cautions about “increased risk of respiratory depression and death” when opioids are combined with benzodiazepines or other CNS depressants. The CDC’s 2016 prescribing guidelines nudged prescribers away from co‑prescribing, leading to a 15 % drop in concurrent prescriptions between 2014‑2018.

Yet, 2020 data still show that 10.2 % of chronic opioid patients get high‑risk benzodiazepine prescriptions. Future solutions point toward personalized risk scores and pharmacogenomics. A 2022 Bayesian model predicted suicide risk with 89 % sensitivity when SSRIs were mixed with other CNS agents, while CYP450 testing could cut dangerous combos by 22 % in vulnerable genotypes.

Industry insiders forecast that by 2025 every major EHR system will enforce mandatory alerts for lethal CNS depressant pairings - a move that could shave up to 35 % off adverse‑event rates according to current pilot data.

Take‑away checklist for patients and caregivers

- Write down every medication, over‑the‑counter product, and herbal supplement you take.

- Ask your prescriber whether any two items belong to the CNS depressant class.

- Never combine prescription sedatives with alcohol or recreational drugs.

- Schedule a medication review at least twice a year.

- Watch for the warning signs listed above; act fast if they appear.

- Consider non‑pharmacologic alternatives for insomnia or anxiety (e.g., CBT, sleep hygiene).

Following these steps can dramatically lower the odds of a life‑threatening interaction.

What makes combining opioids and benzodiazepines especially dangerous?

Both drug families amplify GABA activity, causing a synergistic slowdown of breathing. The FDA reports a 2.5‑ to 4.5‑fold rise in overdose death compared with using an opioid alone.

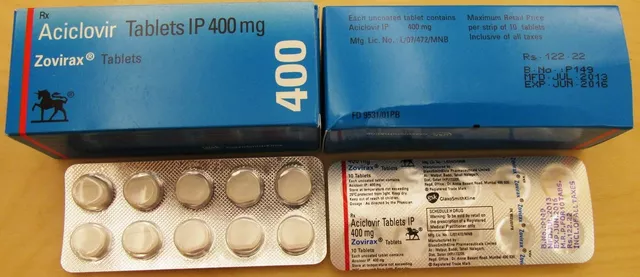

Can over‑the‑counter sleep aids cause the same risk?

Yes. Many OTC sleep aids contain diphenhydramine, which acts as a CNS depressant. When mixed with alcohol or prescription sedatives, they add to the cumulative depression effect.

How can I safely stop a benzodiazepine that I’ve been taking for years?

Never quit abruptly. Work with a doctor to taper the dose slowly-usually reducing by 10‑25 % every one to two weeks-to avoid withdrawal seizures and severe anxiety.

Are there any quick tests to know if I’m at high risk for dangerous interactions?

Pharmacogenomic panels that assess CYP450 enzymes can flag patients who metabolize opioids or benzodiazepines unusually slowly, indicating a higher chance of buildup and respiratory depression.

What should I do if I suspect someone is overdosing on multiple sedatives?

Call emergency services immediately. Keep the person awake if possible, place them on their side, and do not give them food or drink. If you have naloxone and know the person used opioids, administer it while waiting for help.

8 comments

Cheyanne Moxley

If you think mixing drugs is just a personal choice, think again-people die because of reckless combos.

Kevin Stratton

We often talk about freedom, but freedom without awareness is a dangerous illusion. The brain’s GABA system isn’t a playground, it’s a tightly regulated network. When you combine sedatives you’re essentially turning the volume up on inhibition until the system drowns out vital signals :) . That’s why hospitals see a surge in emergency visits after cocktail‑style prescriptions. Understanding the chemistry helps us respect the limits, not just chase a quick fix.

Lionel du Plessis

CNS depression synergy is additive due to GABA‑A receptor occupancy resulting in pharmacodynamic potentiation. Opioid‑benzodiazepine combos increase respiratory drive suppression exponential not linear. Clinicians rely on PK/PD modelling to predict risk thresholds. Real‑world data shows spikes in mortality when dose‑escalation exceeds safe limits.

Andrae Powel

First off, I want to acknowledge how overwhelming all this information can feel, especially if you or a loved one are navigating multiple prescriptions. The good news is that there are concrete steps you can take right now to reduce the danger. Start by creating a comprehensive list of every medication, over‑the‑counter product, and supplement you take – write it down or use a digital app, whichever works for you. Bring that list to your next doctor’s appointment and ask for a thorough medication review; many clinicians will flag risky combinations they might have missed. If you’re on an opioid, ask about a tapering plan; slowly reducing the dose by about 10‑20 % every one to two weeks can significantly lower the risk of respiratory depression. For benzodiazepines, consider switching to a non‑benzodiazepine anxiolytic or exploring non‑pharmacologic options like cognitive‑behavioral therapy, which has been shown to improve anxiety scores without the sedation side‑effects. Keep an eye out for warning signs such as extreme drowsiness, slurred speech, or a sudden drop in breathing rate – if any of these appear, call emergency services immediately. It also helps to avoid alcohol entirely while you’re on any CNS depressant; the combination is a known recipe for disaster. If you’re an older adult, discuss the Beers Criteria with your provider; they can help you discontinue medications that are flagged as high‑risk for falls and cognitive decline. Finally, consider asking about pharmacogenomic testing; certain CYP450 variations can make you metabolize opioids or benzodiazepines more slowly, increasing the chance of buildup and overdose. By taking these proactive measures, you’re not only protecting your health but also easing the burden on the healthcare system.

Leanne Henderson

Wow, what an eye‑opening post!!! 🌟 It really drives home how critical it is to keep track of every single pill, supplement, and even that occasional glass of wine – especially for seniors!!! The checklist you included is spot‑on, and I’d add a reminder to set up a yearly medication review with your primary care doctor – it’s a lifesaver!!! Also, think about buddy‑systems: have a family member or close friend double‑check your meds – two heads are better than one!!! Also, consider using a medication app that sends alerts for potential interactions!!!

Greg Galivan

Honestly this whole thing is overblown – people just need to read the label and stop being idiots.

Edward Brown

Maybe the pharma giants dont want you to know that the warnings are just a cover for pushing even more addictive drugs they control.

ALBERT HENDERSHOT JR.

While it’s understandable to be skeptical, the data from the FDA and CDC are based on extensive peer‑reviewed research. Collaborative efforts between clinicians and regulatory agencies have already reduced concurrent prescriptions by a measurable margin. Continuing education and transparent communication remain essential to safeguard patients.