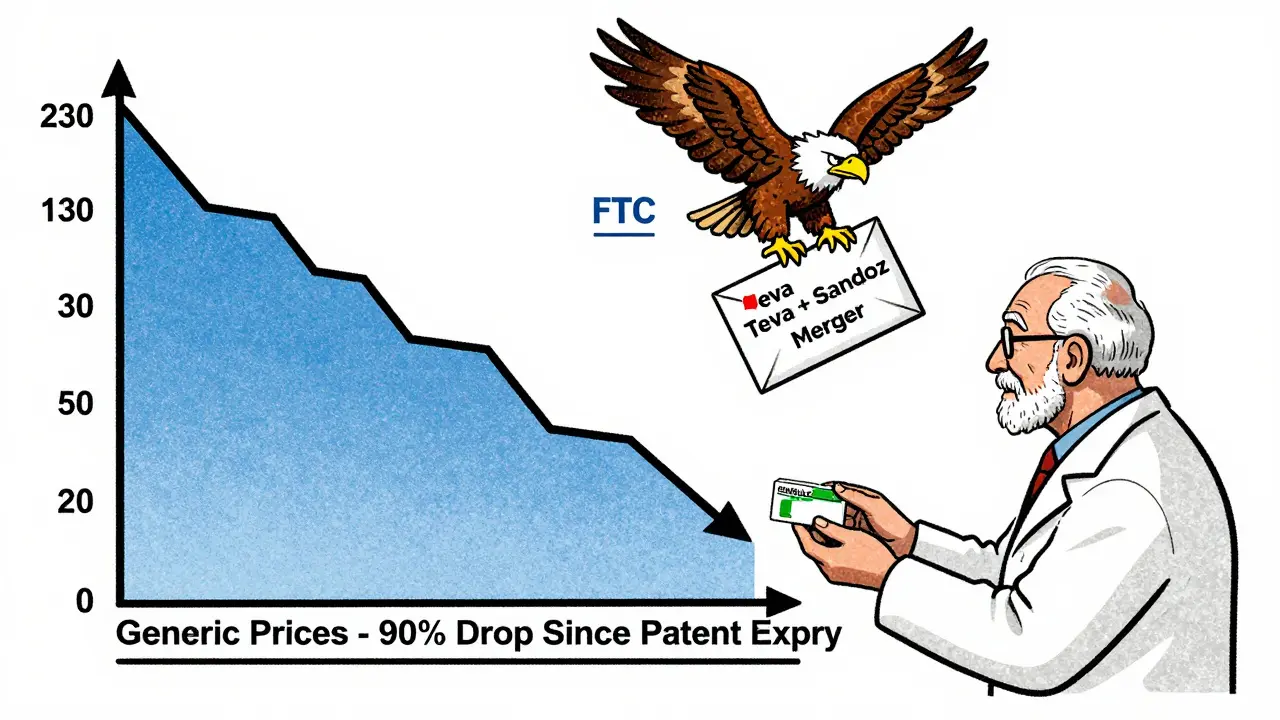

When you pick up a generic version of your prescription, you’re paying maybe $5 for a drug that once cost $100. That’s not luck. It’s the result of a carefully designed system that lets competition do the work - not government price setters. In the U.S., generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions but only 23% of total drug spending. That’s because once a brand-name drug’s patent expires, multiple companies jump in to make the same medicine, and prices plummet - often by 80% to 90% within two years.

Why Governments Don’t Set Generic Drug Prices Directly

You might think the government steps in to cap prices for generics, like it does for some brand-name drugs under the Inflation Reduction Act. But it doesn’t. And for good reason. The FDA and Medicare officials have found that generic markets work better without price controls. When three or more companies make the same generic drug, prices stabilize at just 10% to 15% of the original brand price. No regulation needed.

The 2024 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) report showed that Part D plans pay generics 15% below the Average Manufacturer Price, thanks to negotiated rebates. For preferred generics, those rebates average 28%. That’s market power at work - not government mandates. The Congressional Budget Office confirmed this in 2023: applying international price benchmarks to generics would save Medicare only $2.1 billion a year, compared to $158 billion from targeting brand-name drugs.

Even the 2025 Most-Favored-Nation Executive Order, which targets high-cost branded drugs like Ozempic, makes no mention of generics. Why? Because Americans aren’t paying three times more for the same generic pill made in the same factory. They’re paying pennies.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: The Secret Weapon Behind Low Generic Prices

The real engine behind affordable generics isn’t a price cap - it’s the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before this law, generic manufacturers had to repeat the same expensive clinical trials brand-name companies did. That made it nearly impossible to enter the market. Hatch-Waxman changed everything. It created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway, letting generics prove they’re bioequivalent - not brand new.

That cut development costs from $2.6 billion for a new drug to just $2-3 million for a generic. Suddenly, dozens of companies could make the same pill. The FDA approved 1,083 generic drugs in 2023 alone - a 35% jump since 2017. That’s not a coincidence. It’s policy in action.

Today, the FDA’s Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA), funded by $750 million in industry fees through 2027, is speeding things up even more. The goal? Cut approval time from 18 months to 10. They hit 92% compliance in 2023 for standard generics. For complex drugs - like injectables or inhalers - it’s harder. Only 38% met the 10-month target. That’s why the FDA launched a new submission template in late 2023. Pilot programs cut review times by 35%.

Competition, Not Control: How the FTC Keeps Generic Markets Fair

But competition doesn’t always happen naturally. Sometimes, brand-name companies pay generic makers to stay out of the market. These are called “pay-for-delay” deals. In 2023, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) challenged 37 of them. That’s not just legal action - it’s economic rescue. The FTC estimates these challenges could save consumers $3.5 billion a year by getting cheaper generics to market faster.

The FTC doesn’t just fight pay-for-delay. In January 2024, they blocked the proposed merger between Teva and Sandoz - two of the world’s biggest generic makers - because it would have reduced competition for 13 key drugs. That’s rare. Most mergers get approved. But not when they threaten generic pricing.

And it’s working. A 2021 FTC study found that in markets with three or more generic manufacturers, prices stay low and stable. No price controls needed. The market self-corrects.

What Happens When Generic Prices Drop Too Low?

There’s a flip side. When prices fall too far, manufacturers walk away. In 2024, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists found that 18% of hospital pharmacists had experienced shortages of critical generic drugs. Why? Because the price was below the cost to make it. One drug - doxycycline - saw its price drop to 15 cents a pill. The manufacturer shut down production. Another, phenytoin, disappeared from shelves for months.

This isn’t about greed. It’s about economics. Making a pill costs money - raw materials, quality control, packaging, distribution. If the price doesn’t cover that, companies stop. The FDA’s 2023 Drug Shortage Report showed that only 0.3% of generics spiked in price. But 12% of shortages were linked to unprofitable pricing.

That’s why the FDA now has a program called Competitive Generic Therapy (CGT). It gives fast-track approval to generics entering markets with too few competitors. If only one company makes a drug and it’s cheap, the CGT designation helps others jump in before it disappears.

Real People, Real Prices: What Patients Actually Pay

Most people don’t notice the system working - because it works too well. The 2024 KFF Consumer Survey found that 76% of people on Medicare Part D pay $10 or less for their generic prescriptions. Only 28% pay that little for brand-name drugs. Eighty-two percent of generic users say their meds are affordable. Only 41% of brand-name users feel the same.

On Drugs.com, 87% of reviews for generic drugs mention “affordable” or “cost-effective.” Only 5% complain about pricing. But when a price spike hits - like sertraline jumping from $4 to $45 - it makes headlines. That spike wasn’t due to manufacturing costs. It was due to a single supplier dominating the market. The FDA and FTC stepped in. Within six months, three new manufacturers entered. Price dropped back to $6.

This isn’t common. But when it happens, the system responds - not with price caps, but with more competition.

Why Other Countries Do It Differently

Compare the U.S. to Europe or Japan. In those places, governments set price ceilings. In the U.S., we have 14.7 generic manufacturers per drug on average. In Europe, it’s 8.2. In Japan, just 5.3. More competitors mean lower prices. The U.S. generic market is worth $449.7 billion globally, but we account for 42% of volume and only 29% of value. That’s because we have more competition - and lower prices.

Other countries get cheaper drugs - but they also get longer waits. In Canada, it can take over a year for a generic to arrive after a patent expires. In the U.S., it’s often under six months. Speed matters. Faster access means faster savings.

The Future: Faster Approvals, Fewer Barriers

Looking ahead, the FDA’s 2024-2026 Generic Drug Implementation Plan focuses on two things: complex generics and authorized generics. Complex generics - like nasal sprays or long-acting injectables - are harder to copy. The FDA is building tools to help manufacturers navigate them faster. Authorized generics - brand-name drugs sold under a generic label - are being monitored to stop brand companies from blocking competition by launching their own cheap version right when the patent expires.

The CMS Interoperability and Prior Authorization Rule, issued in April 2024, will stop insurance plans from forcing patients to jump through hoops just to get a generic. They estimate this will save beneficiaries $420 million a year. No price cap. Just removing barriers.

The Congressional Budget Office predicts generic prices will keep falling at 3.5% a year through 2030. Branded drugs? Just 0.8%. That’s not magic. It’s competition. And it’s working.

Why doesn’t the government set prices for generic drugs like it does for brand-name drugs?

The government doesn’t set prices for generics because competition already drives them down - often to 10-15% of the original brand price. Multiple manufacturers enter the market after patent expiry, and prices fall naturally. Studies show that adding price controls would save very little - under $2 billion annually - while risking shortages. The system works better when regulators focus on removing barriers to competition, not setting price ceilings.

Are generic drugs always cheaper than brand-name drugs?

Yes - but not always by much, and sometimes only after competition kicks in. Right after a brand drug’s patent expires, the first generic may cost 30-50% less. But once three or more companies start making it, prices drop to 80-90% below the brand. In some cases, if only one generic is available, prices stay higher. That’s why regulators monitor markets and encourage new entrants.

Can generic drug prices suddenly go up?

Yes, but it’s rare. Price spikes usually happen when only one or two companies make a drug and one shuts down production - often because the price is too low to cover costs. These are isolated cases, affecting less than 0.3% of generics. The FDA and FTC respond by encouraging new manufacturers to enter the market. In most cases, prices return to normal within months.

What’s the difference between a generic drug and an authorized generic?

A generic is made by a different company after the brand’s patent expires. An authorized generic is made by the original brand company - but sold under a generic label, often at a lower price. Brand companies sometimes use authorized generics to block competition by flooding the market early. Regulators now track these closely to prevent anti-competitive behavior.

Why do some generic drugs keep disappearing from pharmacies?

When the price of a generic drops below the cost to make it - including quality control, packaging, and distribution - manufacturers stop producing it. This happens most often with older, low-cost drugs like antibiotics or thyroid medication. The FDA tracks these shortages and uses programs like Competitive Generic Therapy to speed up approval for new makers. But it’s a delicate balance: too low a price kills supply.

What You Can Do

If you’re paying more than $10 for a generic, ask your pharmacist if there’s another manufacturer. Switching brands can save you 20-50%. If your drug keeps running out, report it to the FDA’s Drug Shortage Portal. And if you’re on Medicare, check your plan’s formulary - preferred generics often cost less than $5. You don’t need a price cap. You just need to know how the system works - and how to use it.

14 comments

lokesh prasanth

generic prices low because companies are dumb enough to make pennies. capitalism is a pyramid scheme.

MARILYN ONEILL

so basically the government is lazy and let's drug companies fight like raccoons in a dumpster? genius. i'm sure the poor are thrilled.

Yuri Hyuga

This is how free markets should work! 🚀 Competition isn't chaos-it's clarity. When more players join, prices drop, access improves, and innovation follows. No bureaucracy needed. Just let smart people build better pills. 💊✨

Roisin Kelly

lol so the FDA is just a puppet for Big Pharma? you think they don't control this whole system? they let ONE company make a drug, then let it disappear, then 'oh no we need a new manufacturer'-it's all staged. 🤡

Rod Wheatley

I've been a pharmacist for 22 years. The Hatch-Waxman Act? Game-changer. The FDA's GDUFA? Lifesaver. But when a $0.15 pill gets made in a factory with no quality control? That's when people die. We're not against low prices-we're against unsafe ones. 🙏

Jerry Rodrigues

interesting. i didn't know generics worked this way. makes sense. no drama.

Glenda Marínez Granados

So we celebrate the fact that the market 'self-corrects'... but only after someone dies because their thyroid med vanished for 6 months? 😏 The invisible hand? More like the invisible corpse. 💀

Jarrod Flesch

I'm from Australia-we got price caps here. Took 14 months for my generic sertraline to arrive. Here? Probably 3 weeks. I'll take the chaos over the wait. 🇺🇸✌️

Barbara Mahone

The data presented is statistically sound. The structural incentives align with economic theory. The regulatory framework, while imperfect, demonstrates adaptive governance.

Kelly McRainey Moore

I pay $3 for my blood pressure med. So happy this system works. 😊

Stephen Rock

you people are idiots. the government controls everything. this is just the illusion of choice. they want you to think it's free market so you don't riot.

Amber Lane

My mom had to go without her seizure meds for two weeks. That's not 'competition.' That's neglect.

Samuel Mendoza

So you're saying the system works? But then why did my dad's diabetes drug jump from $8 to $120 overnight? Oh right-only one manufacturer left. Guess competition failed. Again.

Rod Wheatley

That spike? That's exactly why the FDA has the CGT program. Within 5 months of that price jump, three new applicants filed. Now it's back to $6. The system didn't fail-it responded. We just need to tell people it works.