Radioactive Iodine Treatment: What You Need to Know

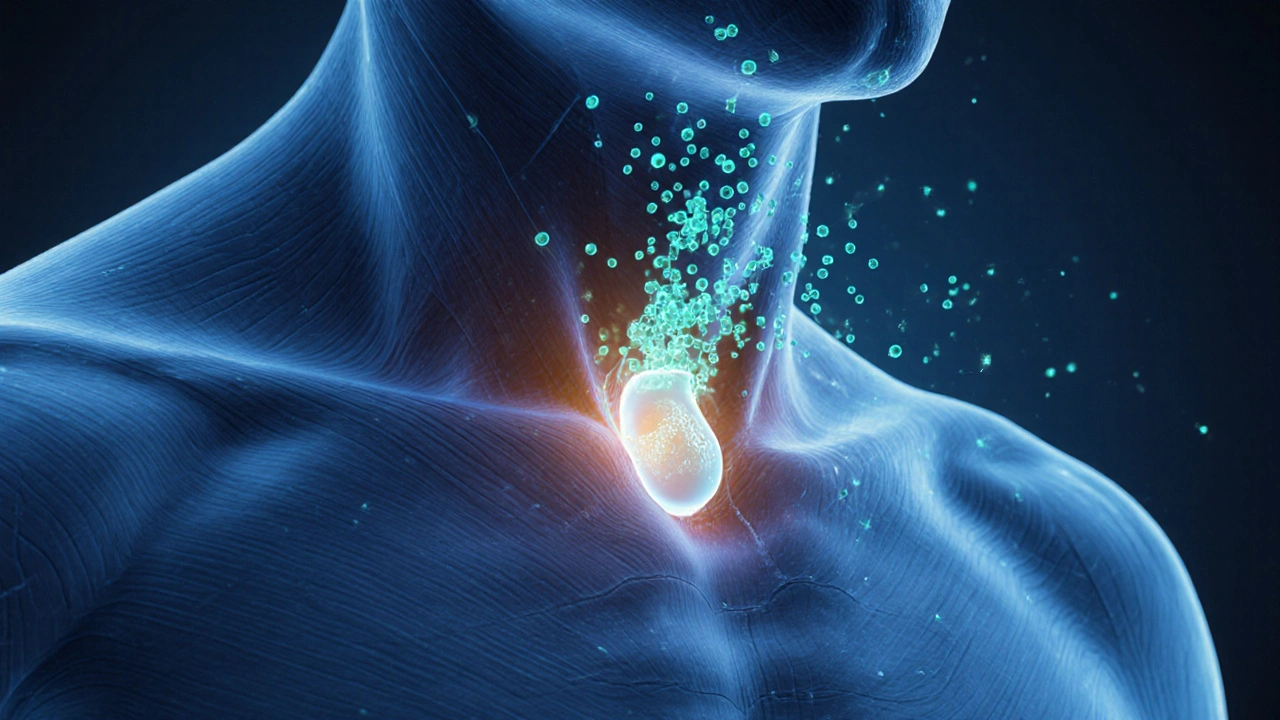

When working with radioactive iodine treatment, a targeted therapy that uses I‑131 to destroy thyroid tissue. Also known as I‑131 therapy, it’s commonly used for thyroid cancer and hyperthyroidism.

One of the main reasons doctors prescribe this therapy is to manage thyroid cancer, malignant growths that arise from thyroid cells. By delivering a precise radiation dose, the treatment can shrink or eliminate residual cancer after surgery. In many cases, patients avoid repeat surgeries because the radioactive iodine reaches tissue that is hard to remove surgically. This link between therapy and cancer control is a core benefit for many.

Another frequent indication is hyperthyroidism, an overactive thyroid that produces excess hormones. Here, the same I‑131 dose selectively destroys over‑active cells, lowering hormone output without removing the gland. The therapy therefore reduces the need for lifelong antithyroid drugs, offering a one‑time solution that many patients prefer.

Key Aspects of Radioactive Iodine Therapy

Accurate dosimetry, the calculation of radiation dose tailored to each patient, is the backbone of safe treatment. Dosimetry determines how much I‑131 will be effective while keeping side effects low. It involves measuring thyroid uptake, body weight, and renal function, then applying standard formulas. Proper dosing ensures the radiation reaches cancerous or over‑active tissue without excess exposure to surrounding organs.

Preparation steps are straightforward but critical. Patients typically follow a low‑iodine diet for 1–2 weeks before the dose, which boosts the thyroid’s ability to absorb the radioactive iodine. Some doctors also ask for thyroid‑stimulating hormone (TSH) elevation, either by withholding thyroid medication or using recombinant TSH injections. This elevation improves uptake, making the treatment more effective.

Side effects are often mild but worth knowing. Common reactions include dry mouth, neck tenderness, and temporary changes in taste. A small percentage experience nausea or a sore throat as the thyroid tissue inflames. Long‑term risks, such as reduced salivary gland function or rare secondary cancers, are tracked through follow‑up labs and imaging. Understanding these possibilities helps patients weigh benefits against drawbacks.

Monitoring after therapy is just as important as the dose itself. Blood tests for thyroid‑stimulating hormone, free T4, and thyroglobulin (especially in cancer patients) are performed at regular intervals. Imaging, like whole‑body scans, can confirm that residual tissue has taken up the iodine and that no unexpected hotspots remain. Consistent monitoring creates a feedback loop that guides any additional treatment if needed.

For those who cannot undergo radioactive iodine—perhaps due to pregnancy, severe iodine allergy, or very low uptake—alternatives exist. External beam radiation, targeted kinase inhibitors, or continued antithyroid medication can fill the gap. Each option carries its own profile of effectiveness and side effects, so a personalized discussion with an endocrinologist is essential.

Overall, radioactive iodine treatment sits at the intersection of nuclear medicine, endocrinology, and oncology. It requires careful patient selection, precise dosimetry, and diligent follow‑up to achieve the best outcomes. Below you’ll find a curated collection of articles that dive deeper into each of these topics, from preparation tips to managing side effects and interpreting post‑treatment scans. Use them to fine‑tune your understanding and make informed decisions about your care.

- Oct 5, 2025

- Posted by Cillian Osterfield

Radioactive Iodine Treatment for Thyroid Cancer: How It Works, Side Effects & Recovery

Learn how radioactive iodine (I‑131) works for thyroid cancer, preparation steps, side effects, and post‑treatment follow‑up in clear, practical terms.

Categories

- Health and Wellness (72)

- Medications (70)

- Health and Medicine (28)

- Pharmacy Services (12)

- Mental Health (9)

- Health and Career (2)

- Medical Research (2)

- Business and Finance (2)

- Health Information (2)

©2026 heydoctor.su. All rights reserved